On an animated film editing is an often changing beast.

As a story artist I often find myself being the first editor of a scene or sequence, cutting being one of the tools in the story artist's and storyboarder's kit. Yet being able to cut a scene, chose the best camera options, give a sequence pace and rhythm does not make a storyboard artist an editor.

For that you need the ability to have an overview of the whole story, it's arch, the character's drives and motivations, track the emotional core of story and character alike, pulling, tugging, ordering and reordering, adding, taking away, shaving, trimming and at times roughlessly cutting away at what will eventually become the final film.

Editors impose form, structure and logic and what they chose to take away is as pivotal as what they chose to keep.

As director and main story artist on Yellowbird a lot of cutting and reordering was part of my daily work, from script to the voice recordings I often found myself trying to play around with the scenes, the order of dialogue, tease out the best possible scenarios, words, beats and gags.

Yet I could not have done this, and the rest of the work without the aid of the wisdom and calming presence of my editor Fabienne Alvarez-Giro and the hard work of our first editor Cedric Chauveau.

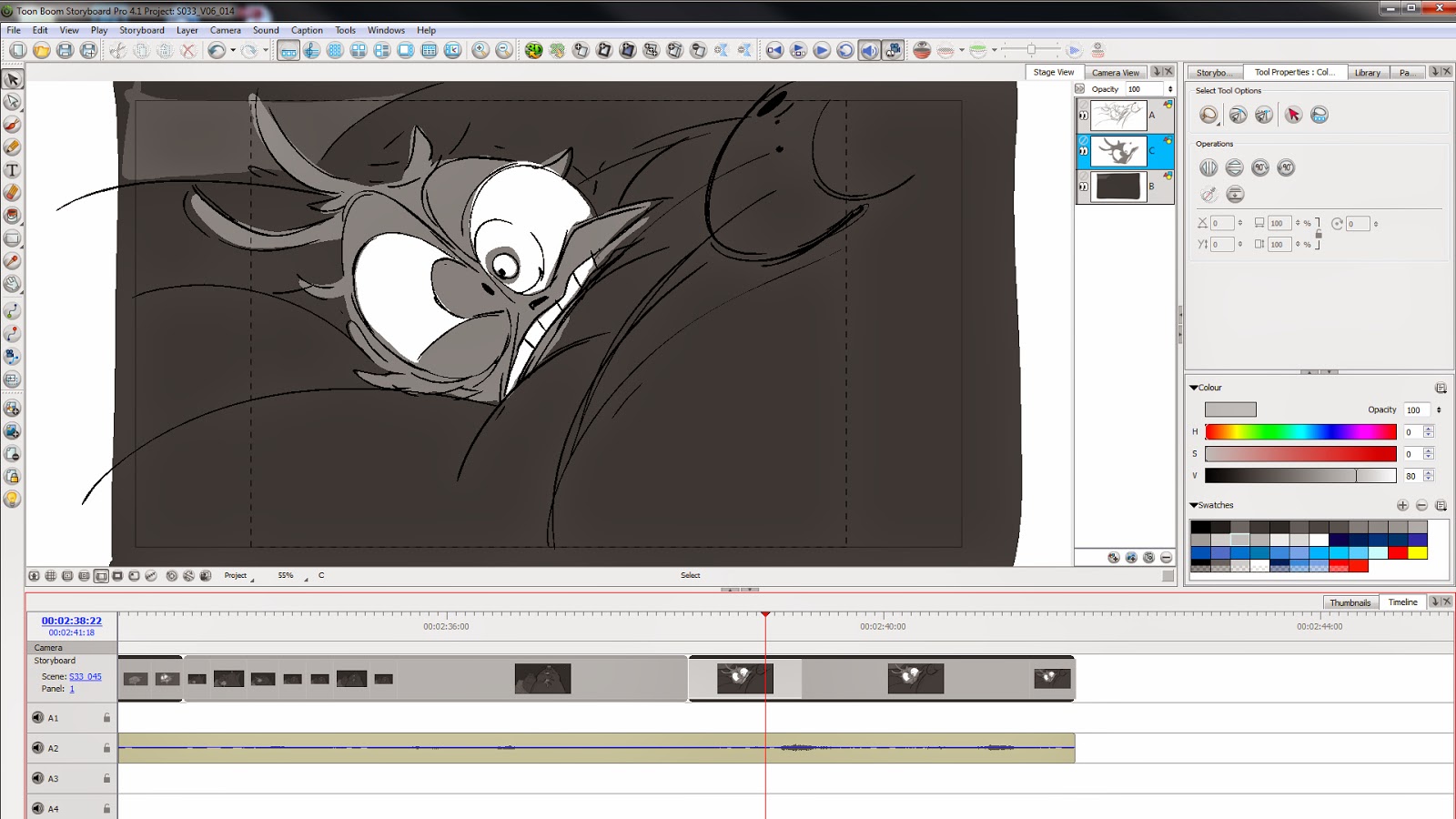

For those of you who don't know, in animation the editing of a film is done firstly on the animatics.

At its simplest, an animatic is a series of storyboard panels, edited together and displayed in sequence with rough dialogue, at times recorded by the storyboarders themselves as the actors have not been involved yet, and/or rough soundtrack added to the sequence of still images to test whether the sound and images are working cohesively and effectively together.

At its simplest, an animatic is a series of storyboard panels, edited together and displayed in sequence with rough dialogue, at times recorded by the storyboarders themselves as the actors have not been involved yet, and/or rough soundtrack added to the sequence of still images to test whether the sound and images are working cohesively and effectively together.

A scene can be worked and reworked dozens of times, new voices added, lines of dialogue changed, then the actual actor's voices added; it is a very organic process and prone to many changes.

The animatic process can be a fairly long one as each scene is slowly put together, through storyboards, then sound, then cleaner and clearer drawings, until a final cut of each scene and sequence is achieved and finally approved by all: director, producers, and even distributors and investors.

Yellowbird arrives at a beach in Holland and is struggling with his conscience, his heart split between wanting to tell the flock and Delph the truth about his deceipt, and the blossoming affection he is starting to feel for Delph.

I previously edit all recorded audio performances by the actors into a sort of radio play, picking out of the numerous takes the ones I prefer, or go best together, in a fluid, rhythmic way even. Sometimes splicing together different takes of the same line to create the perfect one.

Once a scene's dialogue audio track is constructed we export the files as WAVS and import these into ToonBoom. The ability to use the audio when storyboarding greatly increases the power to find the true pace and rhythm in a scene: it is from the actor's performances that you find the character's true emotions and are able not only to draw the expressions and poses needed to emote these, but also to fit everything into a fluid rhythm.

I often cut to the rhythm within the dialogue, a rhythm created in assembling the recorded dialogue. This is a luxury that in live action you do not get, but in animation is absolutely necessary to grasp the accents needed to animate characters succesfully.

It is only after the film is fully completed in an animatic form that lay-out, pre-vis and then animation can start. Storyboarding and editing these into a video-board is the cheapest and simplest option to see if the story and characters work as a whole. If these are not finalized you risk putting into animation scenes which may be cut later, and this is a producer's nightmare as the expense of a 5 minute fully animated and rendered scene greatly outways the cost of a 5 minute animatic.

Though it is not only money that drives animated films to spend so long working on the storyboards and animatics: seeing the whole film as a storyboard on a screen, moving and with sound is the only way to judge if it works, and pursuing all the various avenues a scene, a character, a beat and the story can take is the only way to know if you have made the right choices.

Fabienne helped me immensely in to finding out if the choices I had made were the right ones, and below she explains a little about her work on Yellowbird, and her experiences as editor.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

FG-

I became involved in the project as it was half way through, which

was not a problem for me. On the contrary with a fresh look at the

story and characters, I was able to suggest improvements to certain

elements of the storytelling, some of which were taken into account.

The

way I work is always the same for all the scenes: I first need to

understand its point, the psychology of the characters and the way

they interact along the way. Once I’ve immersed myself fully into

it, I feel at ease to breathe freely with the characters, to suggest

what I feel would work best in terms of scene construction and

rhythm, so that each scene can show its best colors.

A

film has to be considered as a whole, even if that whole is made up

of multiple parts of various intensity and nature which must all

contribute to the overall narration flow.

The above images and the excerpt of the animatic are storyboarded by the greatly talented Julien Perron, who was introduced to me by one of my producers and is currently working at Illumination McGuff, Paris.

CDV-

Your resume` is quite ecclectic, from documentaries to live action

films, TV series and animated features. Do you feel you bring a

particular style to every project you are involved in, or you adapt

to the style of the project and director.

FG-

The directors I’ve worked with for many years tell me that they can

recognize my style. Though I could not define it, it may have to do

with the way I let the scenes breathe, my tempo and a kind of

classism. To work in all kinds of genre is never a problem, on the

contrary it’s quite refreshing to edit different types of programs

such as fiction, documentaries, advertising and animation. I feel

lucky to have that opportunity.

However

I have to say that editing an animation film is always a unique

experience. My first time was with Didier Brunner who called me to

work on “the Legend of Kells”, and my first impression was to

think that there was little to none editing to be done on an

animation film.

At the time I was far from imagining what

working on the «animatic» entices. An animatic is like

pattern to a couture dress, for an animation film, it’s the

backbone of all the animation work done on the film. I was far from

imagining how much freedom there is at that stage, where one can

modify a scene with a pencil, transform the background as if with a

magic wand, or modify a scene structure with a couple of sketches.

However once the scene is locked at the animation stage there is very

little room for change left. It’s always very exciting to have

that ability to change significantly the course of a movie, as we did

when we moved the “Christening” scene of Yellowbird in the

African tree, giving a more upbeat end to the movie thus giving more

sense to the whole adventure these birds had just been through.

Yet my favorite scene in the movie is the one

set in the shipwreck. This entire sequence feels great thanks to the

perfect balance reached between its mood and its rhythm.

Here you find Fabienne's piece in French, its original form.

Arriver

sur le projet en cours de travail ne m'a pas posé de problème

particulier. Cela m'a permis de jeter un regard neuf sur l'histoire

et les personnages et d'être en mesure de faire des suggestions pour

améliorer certains aspects de la narration. Certaines

ont été retenues, d'autres non.

Pour

moi la méthode de travail, quelle que soit la scène, est toujours

la même: bien comprendre la situation, la psychologie des

personnages et les interactions entre eux au moment donné. Après

cette immersion, je me sens le plus libre possible pour

respirer avec les personnages et proposer tout ce qui me semble

judicieux en termes de construction et de rythme pour que

chaque scène donne le meilleur d'elle-même, quelle que soit

sa couleur.

De toutes façons je vois toujours le film comme un tout où certes se succèdent des parties d'intensité et de nature différentes mais qui doivent toutes contribuer à leur niveau au flux narratif global.

De toutes façons je vois toujours le film comme un tout où certes se succèdent des parties d'intensité et de nature différentes mais qui doivent toutes contribuer à leur niveau au flux narratif global.

Des

réalisateurs qui travaillent avec moi depuis plusieurs années

disent qu'ils reconnaissent mon style. Je ne saurais pas bien

le définir mais c'est peut-être dans un rapport à la

respiration, au tempo et à une certaine forme de classicisme.

Passer d'un genre à l'autre ne m'a jamais posé aucun problème,

c'est une forme de rafraîchissement de l'expérience du

montage que de pouvoir l'exercer dans des domaines aussi

variés que la fiction, le documentaire, la publicité et

l'animation. Cet éclectisme est pour moi une chance.

Cependant

travailler sur un film d'animation est toujours une expérience

particulière.

La première fois qu'on m'a proposé de le fa ire

c'était lorsque Didier Brunner m'a appelée pour travailler

sur "Brendan et le secret de Kells" et ma première

réaction avait été alors de penser qu'il n'y avait pas de

montage sur un film d'animation (ou presque pas).

A

l'époque, j''étais loin d'imaginer ce que constitue le travail sur

un animatic, qui est le "patron" (comme en

couture) du film à venir et la référence pour tout le

travail d'animation qui va se faire ensuite. Loin

d'imaginer également de quelle liberté on peut profiter tant

que le travail en est à ce stade et que les modifications se font en quelques coups de crayon et permettent de transposer d'un

coup de "baguette magique" une scène d'un

décor à un autre ou de modifier sa structure avec une

grande fluidité alors qu'une fois que l'animation sera

lancée on ne pourra plus faire de changements qu'à la marge. Cela

donne toujours une sensation d'excitation et d'euphorie que de

pouvoir ainsi modifier significativement le cours du film,

comme cela a été le cas lorsque nous avons transposé la scène

du "baptême" de

Yellowbird dans l'arbre africain et que nous avons ainsi

contribué à

dynamiser la fin du film et à lui donner son sens véritable au regard de l'histoire que venait de vivre cette bande d'oiseaux.

dynamiser la fin du film et à lui donner son sens véritable au regard de l'histoire que venait de vivre cette bande d'oiseaux.

Je pense que mon moment préféré du film est

tout l'ensemble de séquences du Shipwreck. Toute cette bobine est

particulièrement réussie du point de vue de l'atmosphère et du

rythme.